Blair’s Blunderous Blessing

Posted on 02 Dec 2021 by Diwankar Agrawal

Disclaimer: The views expressed below are that of the individual author.

Information underpins democracy, and is “the key to sound decision making, to accountability, and development”.[1]The United Nations (UN) has endorsed freedom of information as a “fundamental human right” and the “touchstone for all the freedoms to which the UN is consecrated.”[2]It is certainly my opinion that openness, transparency, and access to government-held information are the sole remedies for a government ailed with a democratic deficiency.

Notions of ‘informational liberalisation’ aren’t in any way a recent predilection. In the US, for instance, the public’s freedom to information has been present in law since 1966.[3]In the UK, however, such notions acquired currency only during the late-1970s.[4]Nonetheless, it wasn’t long until a commitment to increase government openness began to feature in party manifestos. Notable, for our purposes, is the Labour party’s 1997 vision for the “democratic renewal” of the UK through the “elimination of excessive government secrecy”.[5]

Such enthusiasm was not wholly surprising. Government secrecy was “particularly acute” in the UK: official information was protected in the “widest of terms by criminal law” and frequent use of the “un-justiciable prerogative power”.[6]An example is the infamous Official Secrets Act 1911 (OSA) which prescribed a notorious ‘catch-all’ offence that criminalised seemingly any disclosure by a civil servant which was “contrary to [their] duty”;[7]inspiring the many sardonic retorts that, ‘one would be liable if they revealed how many cups of tea was consumed in a governmental department’.

And with Labour’s victory in the 1997 UK General Elections, the stage was set. MPs were emphatic with their denunciation of this “culture of secrecy” that “permeat[ed] Whitehall”, and were keen on its defenestration in favour of “creating a new culture of openness”.[8]The Freedom of Information Act 2000 (FOIA) was enacted with the objective of effecting a “climate change in the business of administration”.[9]

The FOIA allowed members of the public to request in writing for information held by over 100,000 public bodies covered by the Act,[10]and the covered bodies were under a duty to assist.[11]

Tony Blair welcomed the enactment of the FOIA with zealous admiration: “[The FOIA] will signal a new relationship between government and people” – a relationship of “trust”. However, Mr Blair’s reflection on this decision is absent a drop of exaltation: “You idiot. You naive, foolish, irresponsible nincompoop. There is really no description of stupidity, no matter how vivid, that is adequate. I quake at the imbecility of it”.[12]

While it’s not unusual for individuals to change their views with time, the extreme nature of Mr Blair’s conversion merits further consideration. What inspired this string of self-deprecation? In short, Blair: sage or snollygoster?

I believe it to be the Act’s effectiveness. A number of dramatic disclosures and developments owe their discovery to the FOIA: the 2009 MPs expenses scandal (triggered by a journalist’s FOIA request); the separation of legal advice from national security information which made information about the drone strikes in Syria a qualified exemption – as opposed to absolute; and arguably most important, the ‘reigning in’ of governmental _diktat_by only allowing the executive to veto disclosure requests on the “clearest possible justification”.[13]And for those only persuaded by quantification: 49,961 FOI requests were made in 2018; 91% of them were responded to in a timely manner and 73% of them were resolvable.

The practical impacts of the FOIA are undeniable; the act has been fundamental in altering the “landscape of public activity” and it is of “great constitutional significance”.[14]We revert, then, to the aforementioned question: What inspired Mr Blair’s string of self-deprecation?

Enhanced transparency affected the substitution of the opaque Westminster walls for glass. Unfortunately for Mr Blair, his muck, he could no longer sweep under the rug without the world as his witness. What inspired Mr Blair’s string of self-deprecation? My answer is clear: peevish hypocrisy.

[1]Kennedy v The Charity Commission [2014] UKSC [1].

[2]General Assembly Resolution 59(1), U.N. Doc A/64 (December 14, 1946), p.95.

[3]Patrick Birkinshaw, ‘Freedom of Information and Openness: Fundamental Human Rights’ (2006) 58 Admin LR 177.

[4]Patrick Birkinshaw, ‘Information: Public Access, Protecting Privacy, and Surveillance’ in Sir Jeffrey Jowell and Colm O’Cinneide (eds), The Changing Constitution (OUP 2019) 360.

[5]Labour Party Manifesto: New Labour Because Britain Deserves Better 1997< http://www.labour-party.org.uk/manifestos/1997/1997-labour-manifesto.shtml> accessed 27 November 2021.

[6]Patrick Birkinshaw, ‘Information: Public Access, Protecting Privacy, and Surveillance’ in Sir Jeffrey Jowell and Colm O’Cinneide (eds), The Changing Constitution (OUP 2019) 359.

[7]Official Secrets Act 1911, s.2(1)(b).

[8]HC Deb 27 November 2000, vol.357, col.719.

[9]HC Deb 4 April 2000, vol.347, col.832.

[10]Freedom of Information Act, ss.1 and 4.

[11]Ibid, s.16.

[12]Tony Blair, A Journey(Random House 2010) 516.

[13]R (Evans) v Information Commissioner [2015] UKSC 21 [130].

[14]Patrick Birkinshaw, ‘Information: Public Access, Protecting Privacy, and Surveillance’ in Sir Jeffrey Jowell and Colm O’Cinneide (eds), The Changing Constitution (OUP 2019) 359.

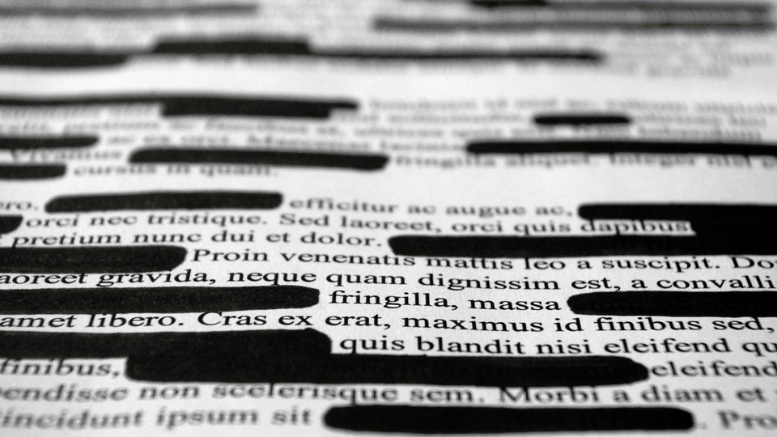

Heading picture source: Studio_Loona, ‘Lorem Ipsum that has been redacted’, Royalty-free stock photo I.D. 321323135, Shutterstock